I have a relative in the hospital right now. He’s fighting an infection, the source of which the doctors can’t quite nail down. I just found out today that he has been in the hospital for the past 3 days. He was asleep when we got there, but his wife was there with him. My wife and I sat down on the couch next to the window while his wife sat in the chair next to his hospital bed. She had a hand to her face while she explained to us what he was going through. As a medical professional herself, she knows how to handle tough situations, but she had a look of genuine worry on her face, even though she tried to hide it. Her husband was breathing softly as the anti-nausea medicine worked its way through his system. The decisive moment came when she told us that she had to call 911 because he was too weak to get up and get into the car. She looked over at him with the love that can only come when you have shared your lives together for 26 years. I had my point and shoot camera, in its case, in my hand. I opened the case before the decisive moment. My instincts were shouting at me to raise the camera, but then they fell silent, which I took as a cue to hold. There was plenty of ambient light in the room as well. It was at the decisive moment that I realized why my instincts had fallen silent – the emotions she was feeling at that moment were hers alone. While I was free to empathize and share her worries, I had no right to steal them without her permission. I quickly cleared my mind and re-engaged in the conversation.

Author: Rick (Page 6 of 17)

The professor crossed into another world today by bringing forth Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. The theorem is actually 2 parts – the first states that no mathematical system can prove every truth about itself while the second states any system that can prove itself using its own logic will contain contradictory statements within that system. It is this first part of the theorem that holds the interesting application to photography (and, perhaps, art in general).

The process of photography is not complete without the photographer. The mind and eye of the photographer shape the image that appears in the viewfinder. The shutter is releases and the scene records, yet there is a piece missing from the frame. That piece is the photographer. It is assumed the photographer is there, but it cannot be proven. In order to prove the photographer, another image (system) must be created in order to prove the photographer’s truth. Of course, this creates a problem because a new system would need to be created in order to prove the complete truth of the preceding image. The photographer cannot validate himself within the image he creates.

Proving everything requires infinity.

Let’s put it another way. The frame provides the boundary in which the image (system) exists. What falls outside the frame is still part of the image. This is so because the photographer (who is part of the image as the creator) made the decision of whether to include it or not in the scene. The system given cannot prove the elements outside the frame. Proving the elements requires a new image (system) to be created. But then some of the elements of the original image cannot be proven (they are part of the new image) as well as those elements, not related to the original image, that were left out of the new image, as they were consciously left out by the photographer.

This application to photography is fascinating. Perhaps, on some unconscious level, we know the above is true, and we (collectively) attempt to record as much as possible through a camera. This is definitely going to require some more thought.

Here is a photograph I took at Rice University a couple weeks ago that demonstrates what I discussed. I chose to exclude the buildings of the Texas Medical Center, which would appear on the right edge of the frame, in this panoramic image of the student quad at Rice University. They are part of the image because of this exclusion, just as I, the camera operator, am part of the image as its creator.

Up to this point, I have only heard 1 dimension of Cartier-Bression’s “Decisive Moment.” The dimension revealed was that the photograph hinged on catching that particular moment that defined the image. I was never aware that Cartier-Bresson wrote in-depth about this topic. Admittedly, I never really looked into it until I had the excerpt from his own writings in front of me. In reading Cartier-Bresson’s own words regarding “The Decisive Moment,” it is revealed that Cartier-Bresson not only looked for that magical moment, but he also obsessed over the composition of the photograph. It still all boils down to that one moment, but this adds depth.

Composition, according to Cartier-Bresson, is a reflexive action – the photographer knows instinctively when everything comes together. It is in that instant that the shutter is released. Of course, there are times when the “snap” of the photo is delayed because the photographer knows that an element is missing (or out of place) that does not complete the composition.

Geometry is also an important factor in composition. It is the geometry that ties all the elements together. This could be seen as conflicting with the “missing” element, but it’s easy to realize that proper geometry may be the missing element that causes the photographer to refrain from releasing the shutter.

Cartier-Bresson, in talking about the Decisive Moment, seems to tell photographers that it’s ok to rely on instinct when shooting. Much like the actions of a soldier in combat or a basketball player on the court, the reflexive knowledge of when the moment is right based on composition is more a product of instinct and training than anything else. This becomes hard to resolve as in art school the students are taught to eschew their instincts in favor of carefully consideration of the scene before them and only shooting after an intellectual analysis has been performed. To wit, one student in class even mentioned that she couldn’t shoot under conditions where she wasn’t able to plan the shots.

A lot of the other photographers we’ve seen up to this point (with some exceptions) in this class have constructed their shots (Rothstein comes to mind) or, in the case of many FSA photographers, have shot according to a script. Cartier-Bresson, while he may have been on assignment (with or without a script), reacted to the scene before him. While I can construct a scene, I find much more freedom in being able to react to what’s in front of me.

One final note – Cartier-Bresson regards cropping as ruinous to photography. It can be inferred that cropping is almost akin to second-guessing one’s instincts as it ruins the flow of what made the photographer release the shutter in the first place. In the very first photography class I ever took, the professor prohibited cropping of any kind on our silver gelatin prints. Her rationale was that we did not learn how to compose in the viewfinder by cropping in the darkroom. This is definitely in line with Cartier-Bresson regarding composition. Cartier-Bresson also opines that a poorly composed photograph is never going to be saved by cropping.

This is perhaps the best example of what Cartier-Bresson is trying to communicate in his essay. The geometric shapes create self-contained units, with each having a quantity of people assigned. The people are arranged in such a way that they form their own discreet lines. Cartier-Bresson is helping us to cultivate the instincts needed to achieve images like this, but how does art school help us in that?

Below are 2 versions of one of my photographs – the original version and the cropped version – taken less than 2 months ago. In this case cropping was necessary in order to remove the camera tilt from the scene. If the camera tilt had remained, the scene would not have been accurately represented in the frame. I wonder if Cartier-Bresson ever had to shoot a football game and find a way to operate within a specific area of the field and under technological limitations (this case being the reach of the lens). Also, let’s not forget that these 2 rather large men are barreling toward me at a rate of speed that does not allow for very quick stopping.

I was driving home this evening, having cursed myself for missing the exit. In my defense, the normal exit has been moved for construction and the signage is a little off from the norm. Ultimately, though, I should have been paying attention to the signs. Not only did that cost me a little more gas, but since I was on the toll road, it cost me $1.75. The sky was orange with the setting sun. At the time there were some low stratocumulus clouds just over the horizon, which were light violet due to their relative position to the sun. Above those were some cirrus clouds, which were to be the stars of this image. The main body of the cirrus formation was a cluster that formed a nearly solid mass of cirrus, making them feel almost solid when looked at. Extending from this main mass were four fingers, all curved and nearly parallel. Just off those fingers were 2 smaller masses of cirrus clouds. The whole scene in front of me, as I waited at the stoplight, appeared as if the hand of a god was reaching to snatch something from the scene. The only problem was my situation – I was driving! The stoplight quickly became a “go” light. By the time I was able to stop long enough to compose a shot, the clouds, as they are wont to do, changed and the image had fleed from existence.

It’s interesting how the title of this post is a palindrome of sorts. Of course, the letters don’t reverse well, but that’s a technicality…

The first 20 minutes of class was spent discussing the War/Photography exhibit at the MFAH. It was prompted by the professor wanting to let us know that the exhibit is closing soon, and that we would benefit greatly from taking it in prior to its exit from Houston. From there various students, who had already seen the exhibit, shared their thoughts of it. We even started to branch out when one started talking about the Oklahoma City memorial. I found her discussion points interesting as she described a part of the memorial I had not visited. Of course, I have made my feelings on the main part of that particular memorial known (click here for a refresher).

Since I’ve seen the exhibit, I’ve had a chance to think a little deeper regarding the exhibit. I’m not talking so much about the exhibit itself, but rather how it relates to the questions asked at the beginning of the semester regarding how I’m affected by constant exposure to a hyper saturated media world.

I mentioned previously that, having been exposed to some rather gruesome wartime imagery in the past, that, aside from a few select photographs, I wasn’t really taken back by any single image I saw on the walls at the museum. At the end I was more impressed with the overall breadth of the exhibit in terms of size and types of pieces it contained. I realized, when I started thinking about it, that my lifetime and my experiences had caused me to become desensitized to the images I had seen 2 weeks ago. The general message I received listening to the other students’ reactions was one of an experience like no other in terms of recording human activity. To say they were moved by this seems to be an understatement.

My age (I’m probably the oldest student in the class) has less to with my reaction than my status as a veteran. Of course, I had more time on this earth in which I could see many of these images and take in other forms “war material,” for lack of a better term. During my chemical warfare training we were exposed to all manner of images regarding the direct effects of chemical weapons on people. It’s still rather difficult to forget the images of men, women, and children who were the victims of blistering agents. The videos of people in uncontrollable convulsions following exposure to nerve agents are also unforgettable. And you could forget about it if you were exposed to blood agents – there was no antidote and the gas mask/chemical suit combination was only effective for a short amount of time before the chemicals began to penetrate. The whole point of seeing these images was drive home the importance of maintaining our gear as we weren’t issued practice gear for exercises – when we got to a new base we were given a gas mask that was to be our protection in the event of a chemical attack.

Curiously, WMD documentation, aside from some photos of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was missing from the exhibit.

Driving home the seriousness of what we were about to learn is important, especially since the threat of an enemy actually carrying out an NBC (the 1990’s terms for WMD) attack at the time was very remote, especially when you take into account a speech by Vice President Dan Quayle in 1990 where he refused to rule out the use of nuclear weapons in response to any chemical attacks by Saddam Hussein in Operation: Desert Shield. With the chemical weapons images and videos (none of which were classified), and the images I saw while certifying as my unit’s SABC instructor, the process of desensitization began. These images were showing direct results of implementations of the weapons of war and subsequent actions needed to ease the suffer, but as time went on, I starting losing my capacity to be appalled by the cruelty of humans, especially in regards to cruelty towards other humans. In 1993 the world bore witness to 2 simultaneous genocide campaigns – in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The images and stories out of those areas also accelerated the process in me.

In 2002 and 2003 we were often treated to videos and still images of the cruelty by the government of Saddam Hussein in the run-up to Operation: Iraqi Freedom. In 2004 I saw the photos of the prisoner humiliations at Abu Ghraib prison. At the time I was appalled, but not nearly so much as a decade earlier. I didn’t even think about the change in my reaction at the time.

All of the images were shown to achieve a desired effect. In the case of the chemical warfare/battlefield medicine images, it was to drive home the seriousness of lessons. In the case of the genocides, Saddam Hussein, and Abu Ghraib, it was to stir sympathy for the victims and outrage against against the perpetrators of the crime. For me, as time has gone on, those effects are less and less powerful.

Does this make me a monster? I don’t think so. I think it makes me human. Just as people who have to see shocking things every day become desensitized to the situations before them, I have become thus by an exposure to the appalling imagery of war. I’m in no way trying to diminish what our paramedics, police, soldiers, et al, do every day. Having been a part of the military, even though I never took part in direct combat, I will never lose my appreciation for what they go through in their daily tasks. It is a little shocking, however, to reflect back on the first time seeing images of this subject matter and comparing one’s reaction to seeing the same types of images 20 years later.

With that I will leave you with a couple of propaganda photographs. Aesthetically, the weapons of war can be very pleasing. There has never been a time in recorded human history that war was not happening somewhere on the planet. Artists are no longer able to romanticize war itself, but they can still impart the beauty of the weapons. Behold the 2 main weapon platforms of the United States Air Force in the 1990’s – the F-15E Strike Eagle and the F-16 Falcon.

The Museum of Fine Arts – Houston is currently hosting a rather large exhibit on photography in war. The pieces themselves date from the modern all the way back to just a few years after the origins of photography. The exhibit itself is very large. In fact, it takes up the entire mezzanine in the Caroline Weiss Law Building of the museum. Contained in the exhibit are mostly prints, but also a few artifacts, such as pieces of camera technology used in combat zones during different periods, some preserved publications, and even some private journals from journalists and military members.

Most of the prints are original, such as the beautiful Daguerreotypes and silver gelatin prints, but there are also some inkjet prints of older photographs. I loved seeing the original prints from the older processes. There were several albumen prints, at least 2 salt prints, 1 carbon print, and, believe it or not, an autochrome print from France during World War I. There is also one photo from the World War II era that is digitally manipulated, but we will get to that one later.

The reactions I’ve gotten from a couple of my peers who have gone to see this exhibit before me were both pretty much the same – the exhibit was wonderful and that their minds were “officially” blown. I had to disregard those reviews so my hopes wouldn’t get too high regarding what I was about to see. I also needed to suppress my own experiences in order to keep that from clouding my judgment regarding the exhibit, which was, of course, going to be the more difficult task. So, with my mind as clean as I could get it, I walked into the exhibit and began to take it in.

The first thing that struck me was the sheer size of the exhibit. I mentioned earlier that it occupied the entire mezzanine in the Law Building. For those of you familiar with the Law Building at the MFAH, then you can appreciate the sheer amount of space dedicated to this photography exhibit. The nearly 3 hours spent walking the exhibit and taking in each piece underscored the importance of war to our history as a species, as well as showing the impact it has on our lives, even if we are far removed from the fighting.

The photos themselves were arranged in a way I would not have initially thought of doing. The exhibit was broken down into different aspects of war, to include recruiting, actual combat, destruction, rest and relaxation, combat fatigue, memorials, et al, rather than by conflict or chronology. This grouping does make sense. The curator of the exhibit needed to strike a balance between highlighting war journalism while also making sure the importance of the messages conveyed by the photographers was not compromised. To have arranged the photographs in a chronological order or to have grouped them by conflict would have merely turned the exhibit into a history lesson.

As for the images themselves, I actually have seen a lot of them before. I recognized many from the “Aftermath: Exhaustion and Shell Shock” area as well as the “Aftermath: Death” areas of the exhibit. Each area contains one image that became iconic for that particular conflict. In the former it was this image of a young officer with a “thousand yard stare” after coming back from an engagement. There is also another rather famous image from the Battle of Gettysburg that shows the battlefield dead. I am a little embarrassed that I cannot provide the photo in question as there are many similar photos of the battlefield dead at Gettysburg and I can’t remember exactly which it is. Interestingly, photography started to come of age in the United States during the US Civil War. The images of the battlefield dead in the US Civil War are often cited as the impetus for the change in public attitude towards war as the camera provided the means by which the actual horrors of war could be conveyed without an artist’s romanticizing a conflict years after it took place.

There is one image in the “Medicine: Wartime Medicine and Medicine Subsequent to War” section that still haunts me. In this area the viewer is treated to photographs of people who are being tended to after suffering wounds in combat, as well as some of the long term treatments that these wounded soldiers need after returning home from battle. Many of these are photos of soldiers with their prosthetic devices (usually legs). There is one large image, the last image in the room, of a mother helping her son out of bed. At first glance one would think this could be an embrace (a function of the vantage point of the shot), but when the detail is examined, it is evident that there is a piece of this man’s head missing. Of course, we can surmise that this former soldier is no longer functional as an individual, and will now be, until the day he passes from this earth, dependent for his very survival on others. I had to ask myself which was the greater cruelty of the war – that he suffered this grave injury or that he was made to survive?

I mentioned earlier that there exists, in the exhibit, one digitally manipulated photo in the “Portraits” area. This was a full body portrait of General Douglas MacArthur standing next to Emperor Hirohito. The artist who submitted the work, however, decided to digitally insert his head on MacArthur’s body. I cannot say that I get why the artist did that, but the greater question was why the curator allowed that particular photograph into the exhibit rather than a reprint of the original image of MacArthur and Hirohito. This one photograph is definitely the weak link in an otherwise excellent exhibit.

I suppose I can’t really say that my mind was blown by this exhibit. In my Air Force days we were shown some pretty shocking gruesome images of the effects of chemical weapons during our chemical warfare training. This was to underscore the importance of the training to our survival on the battlefield. When I was becoming my unit’s SABC trainer, I also had the pleasure of watching video of battlefield triage, battlefield stabilization, and surgery at a MASH unit (all in Vietnam). The amputation was definitely one of the most gruesome things I had ever seen up to and since that point. The execution images are rather haunting, because for many of these they are the point of time just before or after one has crossed into death. In those that don’t feature the condemned about to die, it shows what their physical beings are reduced to in death, be it scrunched in hastily constructed coffins or the bloodstained shirt worn by the condemned as his sentence was carried out. The one that will continue to haunt me, however, is the image I described earlier of the man missing part of his head. The image begs the question I asked at the end of the description, and it’s not one easily answered.

The 1971 film “Johnny Got His Gun” may be streaming somewhere on YouTube or Vimeo. If not, you can order the DVD through Netflix. After you watch that movie, you will understand why I ask that question.

As for now, I leave you with me during my participation in one of the many wartime operation exercises that were conducted in Korea during my time there in 1994 and 1995.

The textbooks were ordered on Wednesday night, but at this point it looks like they’re not going to get here until the day after the next class. This actually sucks, because I wanted to get looking at the material right away. I guess at this point I’m going to have to wing it through the first lecture. They may very well get here prior to the first day of class, but I strongly doubt it as Monday is a Federal holiday.

Of course, the central question today is how I am being affected by all the media that comes at me in the world today, both in ways that I know and don’t know. I have to admit that I found the second part of the question to be one of those frustrating “Is he freaking serious?” type of questions. It still is one of those questions, and it’s not one I think I can answer in a single journal entry. It appears as if Dr. Jacobs is really going to make us think through this course.

That degree of difficulty regarding the second part of the question does nothing to make answering the first part any easier. Self-evaluation sometimes kinda sucks.

As much as we like to think of ourselves as independent thinkers, the constant media barrage has a significant effect on our lives. All of the media to which we are exposed is processed in our minds; that is not something that can be avoided. The end result is determined by how we classify those pieces of media in our minds.

The constant barrage has definitely made me more tolerant of certain subject matters than I would have been in the past. I won’t go into specifics, but my attitudes towards certain things have changed since I was a kid in the middle and late 1980’s, in no small part due to media becoming saturated with a given subject.

I realize that this entry is nowhere near as detailed as it could be. This is going to take some more organization of thought as right now they are all swirling in my head. At this point you can be sure that there are ways that I am affected of which I am aware, but as the thought process for this entry progresses, the swirl of ideas grows larger and much more difficult to contain. Expect more on this subject in future journal entries. Seriously, my grade depends on this one.

My exposure to media has allowed me to proceed with this project as a thumb in the eye to self-righteous behavior on Facebook.

The first question on the first day of class, after all the syllabus discussions were finished, was simple. What was the first picture we saw after waking up that morning? It seems an innocuous question at first listen. When one actually stops to think about it, however, it becomes one of those things that, unless one has a “photographic” memory, could drive someone absolutely insane trying to remember. In my own case I believe it was the cover to From Uncertain to Blue by Keith Carter (which is on my coffee table and would have been seen in passing as I let my dogs outside for their morning playtime), but to be honest I can’t quite remember.

The question was asked to illustrate the point that in the past decade, we as a society are being inundated with a barrage of different media. Heck, even as I type this entry, I have Facebook open in another browser tab while I’m also listening to a song on my iTunes shuffle (right now it’s “The Gathering Wilderness” by Primordial). On my wall in front of me are four photographs – one from my days in the United States Air Force and the other three being school photos of me, my brother, and my sister. Right now I’m processing seven different pieces of media simultaneously.

Our society is saturated in media. Now it becomes an issue of knowing where I, not just an artist, but an individual, stand in this media-saturated environment in which I find myself living.

The truthful answer is that I do not know. One would think that at this point in my life I would have some sort of idea, but I don’t. I came of age in the time when the saturation was beginning to take hold. In the late 1980’s we had Sony Walkman’s, handheld televisions, and Nintendo Gameboys. The VCR had come down in price to the point that it became a near-universal item found in American homes and cable television was reaching its maximum in terms of coverage. Let’s also not forget the birth of the 24 hour news cycle. A little critical theory concerning media here – it seems that the saturation is coming from the “hot media” (media that requires little in the way of mental engagement by the viewer – movies, video games, sporting events, etc) and is drowning out the “cool media” (media that requires much more in the way of mental engagement – books, comics, etc).

All this adds up to the fact that, even though I knew a time when we weren’t being barraged by media, the delivery systems came in at that critical point in my life where it all integrated seamlessly into my existence. The appetizers of the late 1980’s have become, with the acceleration of the technology behind media delivery, a full buffet that surrounds your table and the selections change by the second.

So where I find myself now is adding to that buffet. The blog and the gallery are acting as my voices in this media saturated world. I don’t really know how loud my voice is as I don’t receive any comments on my entries, even when I ask questions to try to get a discussion going (although I know there are people who read this blog). I also don’t track unique visitors to the sites.

So here I sit, with my blog and my online gallery, and I wonder about my standing. I suppose I could start projecting myself more, in order to gauge the reaction to my own offerings, and quite possibly increase my own standing in this media-saturated world. Of course, there is the fear of the unknown that holds me back a little on that, but that’s another story entirely.

Back to the original thought in this entry, even now I still don’t remember the first image I saw this morning after waking up and I have had 24 hours to think about it. That itself is a testament to the speed and ferocity at which we are fed media. The good news is that the pace at which the delivery systems are changing seems to have slowed, so we can all do a collective breath-catching exercise. Every once in a while, though, something does catch me off guard.

This was one of the few places were I wasn’t getting hit with “hot media,” well, up until this encounter with the gas pump. With this I will leave the entry and address the question of the affect this media saturation has on me, in ways I do and do not perceive.

Happy New Year (and Other Assorted Things)

And Merry Christmas, and Happy Thanksgiving! I’m probably being politically incorrect by mentioning the last 2 in the manner I did, but not saying their proper names is succumbing to groupthink, which is something to which most artists who do fall will not readily admit.

Congratulations first go out to my friends who made it into the P/DM program at the University of Houston. I know they all worked very hard to achieve this goal and I can’t wait to see what they produce in their more in-depth studies of photography as an art form.

Now I want to apologize for going all of December without an update. I had pretty much decided to just chill out for this semester break, and it is mission accomplished. The new semester begins on Monday (as in… TODAY!). I’m taking two classes – 20th Century History of Photography and Fundamentals of Video Art. The video class today was only about 20 minutes. Driving to school took longer than the class, but since it was the first day it’s ok. I have 2 friends in the class, so that should make things a little easier as well. The rest are mainly freshmen and sophomores who are barely into their arts programs. This should prove interesting going forward, but we will see. The photo history course should be very interesting. My Traditional Black and White professor, who is a graduate student at the University of Houston, loved the class last semester and could not say enough about it. The professor is the Director of Graduate Studies for the University of Houston School of Art and comes with quite an impressive Curriculum Vitae (that’s a fancy word for resumé in the art world). I’m definitely looking forward to this one, but not to the 3 hours once per week lecture.

Speaking of school, I finished the past semester with a 4.0, bringing my cumulative since entering UH to 3.76. I hope I can jack that up a little this semester, but we shall see in 16 weeks.

This past Saturday was rather good. I went to the Catherine Couturier Gallery here in Houston to meet Maggie Taylor. For those who may not know, Maggie Taylor is a photographic artist. What she does is take vintage photographs and manipulates them digitally to create very colorful surreal works. Contrast that with her husband, Jerry Uelsmann (yes, that Jerry Uelsmann), who creates surreal black and whites in the darkroom. She was there signing her new book, No Ordinary Days, and exhibiting original prints from the book. If you have never seen an original Maggie Taylor print, then you haven’t really seen her art. The same could be said for Uelsmann… his original silver gelatin prints are beautiful and even then you cannot find the flaws in his masking. I met Ms. Taylor in September of last year at the Houston Fine Arts Fair while she was with the Catherine Couturier Gallery booth (this gallery represents both Taylor and Uelsmann in Houston). I didn’t think she was going to remember me, and I didn’t press it, but I did reiterate that I was a fan of the work of both her and her husband. All in all, I left a few dollars poorer but 1 book and 1 experience richer.

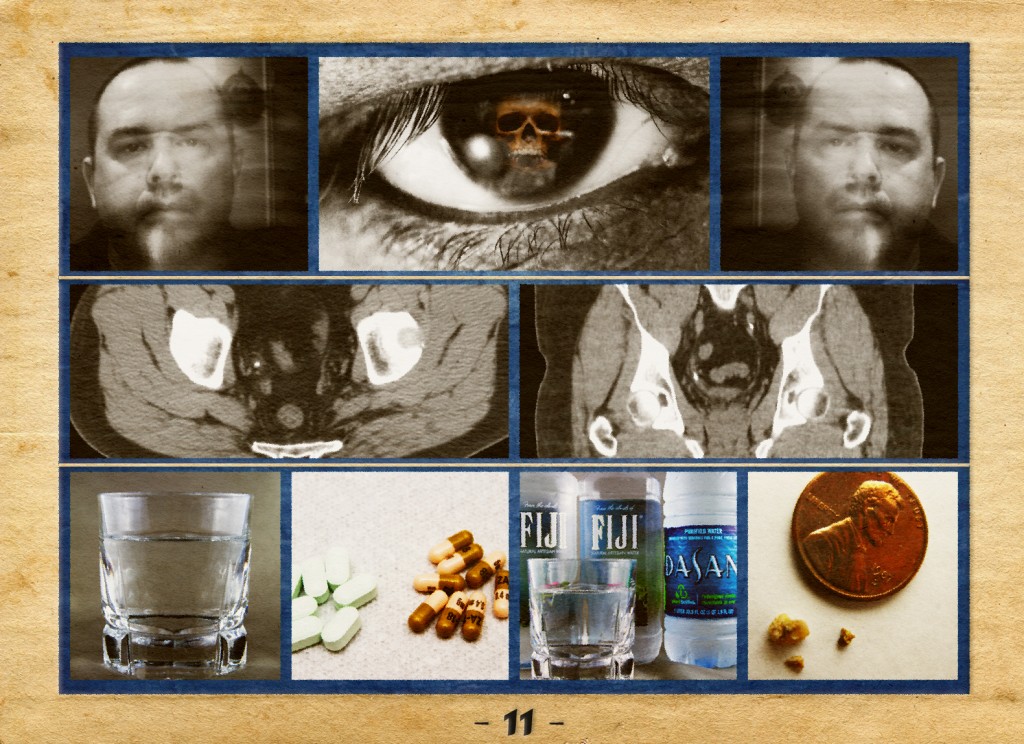

At this point the meeting has inspired me a little to work on my photographic manipulation skills. I have started looking at some of my photographs and have gone on eBay looking for some negatives and photos for sale. I have a few ideas I’m kicking around, and will get started soon. At this point, I will leave you with this piece I completed about a month ago (after neglecting it for about 8 months). Have a good night, everyone, and look for more updates soon.

It’s all around in everyday life. A little pressure is applied here and there and next thing that one realizes is that the choices that one thought he or she made were not really choices at all. Of course, the choice to not follow through exists, but pressure to conform will eventually force one back into the fold. The inevitability of return is almost assured, and if coming back into the fold isn’t an option… well, there are ways to deal with that as well.

The subtle and gentle pressures are applied from birth to death. Vaccinations, school, college or military, work, retirement, death and disposal, these are all common pressures that run through lives in general. Along the way are the details, the permutations of which are too numerous to ponder. In many cases, these are couched as “requirements” in order to advance in a given pursuit.

Legend has it that young and hopeful photographers had to visit Alfred Stieglitz to get his stamp of approval in order to have any success in the world of photography. After Stieglitz died in 1946, the legend goes that Georgia O’Keefe became the ultimate gatekeeper to the world of photography. The level of talent of the artist was not the point, it was impressing these gatekeepers that mattered. If they weren’t impressed, well, then the best thing one could do in order to avoid swimming upstream was to go home and find a new pursuit.

Stieglitz and O’Keefe are no longer the gatekeepers to success in art, but this does not mean that success is any more assured. Now one must fulfill any number of requirements and play any number of games in order to get a toe in the door.

Subtle and gentle pressure. The artist must go to school. The student must pass the judgment of those who “teach” him or her. The student must then stand out in competition but meet criteria set by the judges. The student must then “learn” from these judges in order to earn that piece of paper that says they have passed judgment. But then one is told they must earn another piece of paper that says they have gone through an ultimate judgment, which will propel them to the ranks of those judges.

Never mind the talent level of the artist (or lack thereof). Discipline must be maintained and everyone should be moving toward the same end.

The game must be played. All along the way, pressure is applied in order to keep the person on the path set by those who now oversee that very path, and by whom the criteria for passage is set. The person is told they must take that path. Failure to do so will result in the person not achieving success in the pursuit of their goals.

The pressure is gentle. It’s almost imperceptible. The pressure is great and is there. Eventually, there is nothing but the path as one moves headlong and fast toward the destination. As the pressure increases and constricts, the choice to continue down the path is still present. But one thing remains…

Either way, the event horizon will be crossed.

The Panopticon continues its machinations.